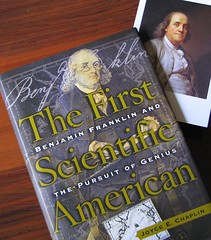

I was telling you last time how much enjoy reading about Benjamin Franklin. Now permit me to mention the umpteenth biography I’ve read about him. Franklin had at least five successful careers: writer, businessman, scientist, civic leader, international statesman. Biographers could probably write book length accounts on each of them as if they were separate people. I’ve been looking for something about Franklin the scientist.

I just finished The First Scientific American [LibraryThing / WorldCat] by Harvard professor Joyce Chaplin. It billed itself as a biography that uniquely examined his science career. Most Franklin bios run the course I laid out in the middle of my last blog, so I was hoping Chaplin’s book would dwell on his scientific period. It didn’t. At first. The first seven chapters, although enjoyable to a Franklinophile like myself, followed the normal outline of most Franklin biographies.

I just finished The First Scientific American [LibraryThing / WorldCat] by Harvard professor Joyce Chaplin. It billed itself as a biography that uniquely examined his science career. Most Franklin bios run the course I laid out in the middle of my last blog, so I was hoping Chaplin’s book would dwell on his scientific period. It didn’t. At first. The first seven chapters, although enjoyable to a Franklinophile like myself, followed the normal outline of most Franklin biographies.

In one of the last chapters, however, Chaplin managed to tie up many little threads she had been quietly weaving into the narrative all along. She accomplished it by presenting Franklin nearing the end of his life and longing for time to answer questions he had posed years earlier; to finish projects he started to research but got called away; to investigate theories he had toyed with.

Americans think of him as a Founding Father. Chaplin maintained that he was first and foremost a scientist. He was on par with Newton among the greats, but all his other “successful distractions” pulled him away from accomplishing even more. He never completely stopped doing science, but it was limited to times when it was convenient. His charting of the gulf stream, for instance, and the world’s first deep sea temperature studies were done while en route to handling pesky international conflicts like the American Revolution.

There’s even a passage Chaplin quotes from 1782, where Franklin — steeped in thoughts of fluid dynamics, the circulation of heat, and the choppy landscape of England — imagines the earth’s interior to be a dense liquid churning about an iron core with the surface “swimming in or on that liquid.” The surface, therefore, was a “shell, capable of being broken and disordered.” It was just conjecture “given loose to imagination,” for which Franklin regretted observation was “out of my power.” But what he wrote is a fair description of modern plate tectonics — almost 150 years before Alfred Wegener’s continental drift theory was laughed at, and almost 200 years before it became established fact.

How can you not be amazed by this guy when book after book reveals something new like that?